They Are All Gone and Thou Art Gone as Well! Yes Thou Art Gone! Matthew Arnold

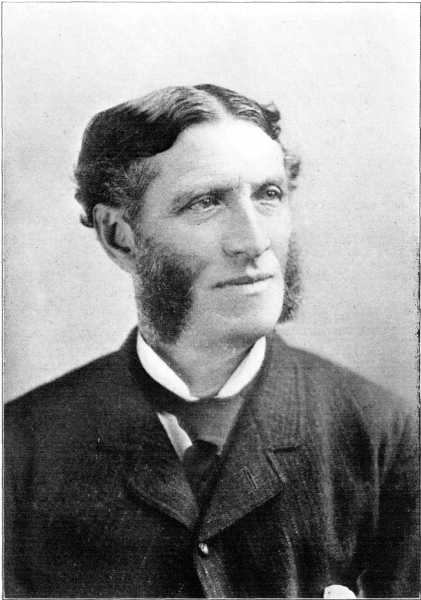

Photograph of Matthew Arnold

In 1843 or 1844, his brother Tom tells united states of america, Matthew Arnold saw a mother and child on a pier in ![]() Douglas,

Douglas, ![]() Mann, and this sighting became the footing for "To a Gipsy Child past the Sea-Shore" (Tom Arnold viii): a venturesome poem, as I will argue, that diverges from the Romantic antecedents it acknowledges by deploying questions to destabilize and transform the rhetorical identity of its speaker. Tom Arnold's mention of the poem in his brother's obituary most 40 years afterward it appeared in The Strayed Reveller (1849) suggests how "Gipsy Child" was admired in its time, but in modern scholarship the verse form receives little attention. Some expert critical discussion centers in its identity every bit i of a group of "Gypsy poems," the others being "Resignation" (1849), "The Scholar-Gipsy" (1853), and "Thrysis" (1866). Lance Wilder, in an essay addressing all four poems, persuasively argues that "Gipsy Child" initiates a series that uses the alterity of the Gypsy, "a sort of wandering signifier," to ponder questions most time and immortality (409). Such thematic estimation illuminates the fluid value to Arnold of the Gypsies' cultural foreignness, and yet a rhetorical strangeness in "Gipsy Child" remains unremarked. Antony Harrison understands the Gypsy to signify Arnold'southward relationship with his readers, suggesting that the figure "develops equally a proleptic metaphor for this human relationship and for Arnold's self-positioning in his prose works of cultural criticism" (122). I share Harrison's involvement in the Gypsy as a figure for audience, simply my discussion focuses on how "Gipsy Child" operates as a lyric experiment. The poem's questions mute its interlocutor, a "child" potentially in possession of his or her own human subjectivity, and turn its speaker into a solitary discourser. Pursuing a reading of "Gipsy Kid" every bit a novel lyric experiment reveals a relationship between its dynamic interrogatory mode and the high value that the more than mature Arnold assigns to dialogue in other aspects of his work, as cultural critic and equally inspector of schools. It too discloses how "Gipsy Child" invites inquiry into the human relationship betwixt real-globe events and poetic representation.

Mann, and this sighting became the footing for "To a Gipsy Child past the Sea-Shore" (Tom Arnold viii): a venturesome poem, as I will argue, that diverges from the Romantic antecedents it acknowledges by deploying questions to destabilize and transform the rhetorical identity of its speaker. Tom Arnold's mention of the poem in his brother's obituary most 40 years afterward it appeared in The Strayed Reveller (1849) suggests how "Gipsy Child" was admired in its time, but in modern scholarship the verse form receives little attention. Some expert critical discussion centers in its identity every bit i of a group of "Gypsy poems," the others being "Resignation" (1849), "The Scholar-Gipsy" (1853), and "Thrysis" (1866). Lance Wilder, in an essay addressing all four poems, persuasively argues that "Gipsy Child" initiates a series that uses the alterity of the Gypsy, "a sort of wandering signifier," to ponder questions most time and immortality (409). Such thematic estimation illuminates the fluid value to Arnold of the Gypsies' cultural foreignness, and yet a rhetorical strangeness in "Gipsy Child" remains unremarked. Antony Harrison understands the Gypsy to signify Arnold'southward relationship with his readers, suggesting that the figure "develops equally a proleptic metaphor for this human relationship and for Arnold's self-positioning in his prose works of cultural criticism" (122). I share Harrison's involvement in the Gypsy as a figure for audience, simply my discussion focuses on how "Gipsy Child" operates as a lyric experiment. The poem's questions mute its interlocutor, a "child" potentially in possession of his or her own human subjectivity, and turn its speaker into a solitary discourser. Pursuing a reading of "Gipsy Kid" every bit a novel lyric experiment reveals a relationship between its dynamic interrogatory mode and the high value that the more than mature Arnold assigns to dialogue in other aspects of his work, as cultural critic and equally inspector of schools. It too discloses how "Gipsy Child" invites inquiry into the human relationship betwixt real-globe events and poetic representation.

"Gipsy Child" begins with a question and values the misreckoning of an expectation of reply. Starting by asking is a loaded move, as John Hollander notes: "Opening questions in verse can carry considerable figurative weight. At the very least, they may presuppose non the usual empty respond (for example, 'Yeah' or 'No' or 'Nobody' or 'Everybody' or the like), but rather some hedged response, like 'You may well ask!'" (Hollander 22). "Gipsy Child"'south interrogative opening—"Who taught this pleading to unpracticed eyes?"—places information technology inside a nexus of poems extending well earlier and across the nineteenth century that begin by asking.[i] For such poems, the meaning of questioning matters very much. As Hollander remarks, "poetic questions" are e'er "tropes of interrogation and inquiry far more figurative than so-called rhetorical questions are" (64). In this opening-question way, William Blake's "The Tyger" is a Romantic antecedent for "Gipsy Child," for not just does it begin with a query ("Tyger Tyger, burning vivid,/ In the forests of the night;/ What immortal hand or eye,/ Could frame thy fearful symmetry?") that interrogates while inviting the reader to envision an addressee, simply information technology as well develops through questioning (1-4). However in addressing its "Tyger," Blake'south poem insinuates from the first that the addressee—an animal, afterwards all—volition not reply, or that a response from the brute will propel u.s.a. into otherworldliness. It too uses a phrase of its opening sentence to innovate its addressee earlier asking anything. "Gipsy Child," on the other paw, articulates its question immediately, without the phrase of introduction characteristic of apostrophe ("O Wild West Wind!"; "Milton!"; "G still unravish'd bride of quietness"), and seems at its opening to adumbrate a existent world—with its dateline-mode indication of setting in "Douglas, Isle of Man"—and to address a figure, the "child" of the championship, from whom a reply might reasonably be expected.

"Gipsy Child" abrogates the expectation of an reply past metamorphosing its speaker from an apparent sharer in dialogue to an isolated figure discoursing to an unhearing audience—or, to a wholly fictive ane. This transformation differentiates "Gipsy Kid" from "Tyger," from the Romantic conversation poem, and from the conventional verse form of apostrophe, for the project of Arnold's poem is to enact this particular dynamism in speakerly identity. To come across this, it will help to recall the verse form's structure.

A generative alternation between query and reflection characterizes its seventeen stanzas, which we can schematically divide into 4 sections. The showtime department, comprising the opening v stanzas, begins with a quatrain of questions:

Who taught this pleading to unpracticed eyes?

Who hid such import in an infant'southward gloom?

Who lent thee, kid, this meditative guise?

Who mass'd, circular that slight brow, these clouds of doom? (1-iv)

The next four stanzas ponder the child's situation, turning attention to the surrounding scene (stanza two), to the child (stanza three), and, in stanza four, to the speaker as an inadequate source of comparative experience ("Glooms that get deep as thine I have non known," 17). Thus the first department creates a sense of setting, suggests the presence of an leaseholder, and establishes the speaker's want to sympathize the kid's status. The poem'south title and dateline nurture a sense of setting and occasion. Another version of the championship, "Stanzas on a Gipsy Kid past the Body of water-Shore, Douglas, Isle of Man," which appears in the contents of The Strayed Reveller (but not, in that book, above the poem itself), was abandoned between 1851 and Poems, Second Series (1854);[2] it implied, with "stanzas on," that the verse form intended more to call the child to mind than to speak to the child. Arnold settled instead on the "to" suggestive of directly address.

The indicate here is not that a revision in title was unique to Arnold—John Keats inversely changed his title for "Ode on Melancholy," for example (Keats 374n)—or that Arnold departs from his Romantic predecessors simply by being preoccupied with problems of intersubjectivity. It is that "Gipsy Child" inhabits these problems and illuminates their pregnant in a quite novel manner. When the poem chooses an addressee who might conceivably hear and answer—a child rather than an animal, an urn, the wind, or a expressionless person—and opens directly with a question, it assigns itself a projection of making the addressee not respond, of dimming a counter-subjectivity. This projection has implications for the speaker's identity and for the human relationship between poet and audience, since the significant of the kid for the speaker influences the meaning of the speaker for readers. In Arnold'south subsequently poems—for although the timeline with his poetry is short, there is an earlier and a later—a mode of meditative cocky-inquiry becomes more fully established, and it might be tempting to impute to "Gipsy Kid" the steadier rhetorical keel of Arnold's subsequent work, reading information technology equally simply a poem of self-questioning, if a rather awkward one. I advise that nosotros resist this revisionary temptation and read "Gipsy Child" as rhetorically unsettled, understanding its unsettledness as a poetic gateway: in Arnold's work, a gateway to the steadier meditative mode of such a poem as "![]() Dover Beach," roughly a middle-period poem on the short timeline, and a transitioning towards a mode of self-questioning equally lyric dialogism.[3]

Dover Beach," roughly a middle-period poem on the short timeline, and a transitioning towards a mode of self-questioning equally lyric dialogism.[3]

The second section of "Gipsy Child" (stanzas six to 10) opens, similar the commencement section, with iv questions, only now these are interspersed with possible answers. The speaker begins to talk to himself, while alluding to the circumstance of awaiting his interlocutor's respond. The basic query, which the verse form seems to address to its "child," is whose condition of tranquility sadness is comparable to yours? In response, the poem recruits various imaginary figures: someone in the mountains listening to "battle suspension below" (23), "some exile'southward" (25), "some angel's" (26), "stoic souls" (29), "some gray-haired king" (33). Yet none offers a suitable comparing. Pacing gains a dynamic variability in this second section, where the questions first come fast as the poem rejects its own replies:

What mood wears similar complexion to thy woe?

His, who in mountain glens, at apex of twenty-four hour period,

Sits rapt, and hears the battle break below?

–Ah! thine was not the shelter merely the fray.Some exile's, mindful how the past was glad?

Some angel'south, in an alien planet built-in?

–No exile's dream was ever half and then sad,

Nor any angel'southward sorrow and so forlorn. (21-28)

And so the questions themselves starting time to grow. Stanza 8 consists entirely of a question, as does stanza ix, which alludes to how the speaker yet awaits a reply, his interlocutor'south sharing of personal "lore":

Or practise I wait, to hear some grayness-hair'd king

Unravel all his many-colour'd lore;

Whose mind hath known all arts of governing,

Mused much, loved life a piffling, loathed it more than? (29-36)

The notion of an answer coming from the child-addressee has non been abased, simply the poem now identifies it equally a fanciful possibility. This stanza insinuates that the verse form may offering stories about how its interlocutor might reply only will non offer dialogue.

In its final two sections, stanzas 11-14 and 15-17, "Gipsy Child" enters the territory of conventional apostrophe; its speaker addresses an entity who (the poem has now decided) cannot hear or respond. Stanza eleven crosses into an apostrophic mode past dividing itself betwixt a two-line exclamation to the child and two questions:

O meek anticipant of that certain hurting

Whose sureness grey-hair'd scholars hardly larn!

What wonder shall fourth dimension breed, to swell thy strain?

What heavens, what earth, what sunday shalt grand discern? (41-44)

As the verse form'southward concluding three stanzas cryptically articulate a prediction most the inevitable persistence of the child's sadness, a volley of second-person pronouns ("thou," 57; "thy," 60; "thee," 61; "thine," 62; "g," 65; "thy," 66, "thou," 67) insists on the presence of a child-addressee, while the lines articulate thought too abstract and cryptic to "really" be addressed to a child. Now, four-fifths complete, the poem finds apostrophe. As this scheme in four parts demonstrates, the action of "Gipsy Child," in many means a poem of stasis—without concrete movement, exchange of words, or even disarming epiphany—lies in experiment with the footstep and mechanics of questioning and answering. How quickly will the questions and the answers come, from whom, and from what (observation? deduction? reflection?) will they derive?

Questions and answers raise the specter of chat, and "Gipsy Child" has affiliations with the Romantic poems that are frequently chosen "chat poems" and that M. H. Abrams classifies (broadening the group somewhat) as "greater Romantic lyric." In its revelation of a speakerly self in transition, "Gipsy Child" resembles such poems as Samuel Coleridge'due south "Frost at Midnight" or "Eolian Harp," or Percy Bysshe Shelley'south "Stanzas Written in Dejection." Coleridge in particular sometimes invokes a tenuously present addressee (his "Beloved Babe" in the former verse form, "pensive Sara" in the latter) in a style that resonates with Arnold'southward treatment of his "child." Yet "Gipsy Child" differs from such poems in categorical ways, every bit Abrams's description of the type shows. The "greater Romantic lyric," he says:

begins with a description of the mural; an attribute or change of attribute in the landscape evokes a varied but integral procedure of memory, thought, anticipation, and feeling which remains closely intervolved with the outer scene. In the form of this meditation the lyric speaker achieves an insight, faces up to a tragic loss, comes to a moral decision, or resolves an emotional problem. (Abrams 77)

In the insignificance of landscape for its speaker, in its insistent invocation of a specific addressee, in how it holds open the possibility for dialogue at its beginning, in the unabating centrality of question and respond, and in its privileging of rhetorical transformation, "Gipsy Kid" does not fit the type—although it might be recognized as an innovation upon information technology, a reflexive poem that meditates, through its questions, on the nature of a questioning identity. There are different kinds of questions, "Gipsy Child" says, and the "same" question can be commencement 1 sort and then some other; the poem's ending casts a new tenor over the opening "[w]ho taught this pleading to unpracticed eyes?" which retrospectively gestures towards an unrealized possibility for dialogue and towards a lyrical road non taken.

Susan Wolfson remarks that questioning is "an informing activity of Romantic language" (21) and suggests that establishing potency through questioning is a gesture characteristic of Romantic poems (20-one). Besides its apply of questions to transform the rhetorical identity of its speaker, what complicates Romantic affiliations in "Gipsy Child"—becoming a very Victorian feature of the verse form—is the vocational significance of its lyrical experiment: how its experiment with questions connects to Arnold's preoccupations in his jobs. As Hollander remarks, "[p]oems talk to, and of, themselves not to evade discourse almost the rest of the world . . . but to enable it" (fifteen), and for Arnold, son of a ![]() Rugby headmaster, the question of questions, the experimental task of discovering productive forms of accost, became key to extra-poetic undertakings as a critic and equally inspector of schools. Here, answers get-go to affair, inside poems and out, and thus dialogue matters as well. What kind of answer might a particular question invite, and from whom?

Rugby headmaster, the question of questions, the experimental task of discovering productive forms of accost, became key to extra-poetic undertakings as a critic and equally inspector of schools. Here, answers get-go to affair, inside poems and out, and thus dialogue matters as well. What kind of answer might a particular question invite, and from whom?

Arnold routinely had forms of accost in mind when he bandage his sharply evaluative heart over poetry. Excluding Empedocles from Etna from his volume of 1853, he made his well-known formulation of the shortcoming in extant pieces of Empedocles, that they offer a sterile and hopeless dialogue, "the dialogue of the listen with itself," instead of "the calm, the cheerfulness, the disinterested objectivity" of earlier Greek poetry (Arnold, "Preface" 185). The imperfect parallelism in the two sides of Arnold's equation—his explicit commemoration of a series of characteristics in the Greek versus the terse conception on the other side—intimates how important and how problematic a subject "dialogue" was. As he continues—"mod problems take presented themselves; we hear already the doubts, nosotros witness the discouragement, of Hamlet and Faust" (186)—Arnold asserts a connection between an undesirable grade of dialogue and the emotional and intellectual struggles that were for him the authentication of contemporaneity.

Less commonly remarked is how, around the time he wrote "Gipsy Child," Arnold was perusing philosophical dialogues that ponder forms of address. His reading lists for the mid-1840s suggest he read Plato's Menexenus tardily in 1845 and probably read the Phaedrus around this fourth dimension (Allott 258-61). Menexenus is unusual amid Plato's writings in that the "dialogue" becomes occasion for presentation of a funeral voice communication that comprises the entire piece; Plato's purposes in appropriating this Periclean oration (and assuasive it to transfigure his own form of address) are still a subject of argue,[4] but clearly Menexenus thinks about rhetorical transformations. In the Phaedrus, Socrates offers 2 discourses on love that differ not only in content simply in manner.[5] Circulating in Arnold's notebooks afterward in his life is a remark on the purpose of dialectic from The Republic, which Arnold probably also read at this fourth dimension, in 1845 (Allott 259), copied there at least three split up times: in 1876, 1885, and in an undated entry (Arnold, Note-Books 258, 419, 504). Information technology comes as Socrates wonders if "the merely accept a ameliorate life than the unjust and are happier." This is an essential question, Socrates asserts in the judgement Arnold quotes once again and again: "For information technology is no ordinary matter we are discussing, only the right conduct of life."[6] This remark then valued by Arnold implies that the correct mode of dialogue can answer primal questions about the correct fashion to live.

Thinking about productive forms of dialogue became a vocation in Arnold'south undertakings equally inspector of schools, the position that earned him a living from 1851 until 1886. How practiced was the "answering" in a item classroom?7 Was there enough questioning and answering? What sort of exchange betwixt teacher and student was nearly productive? David Russell argues that for Arnold an ideal educational activity depended upon an instructor's calculated suspension of certainty in conversation with students:

He proposed an alternative teaching, 1 that eschewed cognition and the power relations that nourish it. Communication, for Arnold, becomes a matter of giving someone something they can employ, rather than transmitting knowledge, or data, to them. This requires an unknowing relation in 1's encounters with others, whether the knowledge relinquished is of the nature of the other, or of the truths to be transmitted. (Russell 137-38)

Adept pedagogical posture, like a verse form, is crafted. In "Gipsy Child," the instability of the speaker's relationship with the "child" centers in the question that informs Arnold's later vision of effective pedagogy: what course of address is virtually productive?

Puzzles of intersubjectivity—and an inquiry into the dialogue that enacts intersubjectivity in verse and in lived experience—prevarication at the core of all these undertakings. Writing to his friend Arthur Hugh Clough late in 1847 or early in 1848, Arnold remarks on the challenge posed to poets by the accumulations of history. "The what you lot have to say depends on your age," Arnold tells his friend—that is, on the epoch in which ane lives—and after poets must digest more man experience than earlier poets. The task is hard: "The poet's matter being the hitherto feel of the globe, & his own, increases with every century. . . . For me yous may oft hear my sinews cracking under the effort to unite matter" (Arnold, Letters 78). As the formal restlessness of Arnold's poems effectually this time reveals—"Gipsy Child" was written soon subsequently "Cromwell," his "dutiful" Newdigate Prize poem in heroic couplets (Murray 49), and George Saintsbury (24) remarked on how in The Strayed Reveller Arnold "makes for, and flits about, one-half-a-dozen different forms of verse"—this synthesis of "matter" entailed intensive negotiations in form. The rhetorical transformation within "Gipsy Child" comprises such negotiation.

Reading "Gipsy Kid," we might experiment ourselves past moving back in time and thinking about Arnold's ain conversations as a kid with William Wordsworth, how Arnold first met the elderberry poet at the age of 8—coincidentally, the age of Wordsworth'south cottage child in "We are Vii"—and how encounters with him and Robert Southey were office of Arnold's enjoyment of his family unit's holiday home at Fox How (Murray 22, 31-two). Might that childhood feel of conversing with poets accept complicated his reading of Wordsworth and his representation of the interlocutor in "Gypsy Kid"? Did talking with poets equally a child influence Arnold's notions of poetic dialogue?

Arnold would have known Wordsworth'due south poems of conversation with children, and to see a mode that "Gipsy Child" invokes just in which it does non share, we might read Wordsworth'southward "We are Vii" (1798). Like Arnold's poem, Wordsworth'south announces early an intent to accost a "Child," but Wordsworth's interlocutor speaks, and her oral communication carries the poem. The opening stanzas pose a thematic problem (how tin can a child have any real understanding of the significance of death?) and communicate a sense of dramatic situation: the child's age, her appearance, the rustic setting of the encounter:

– A Simple Child,

That lightly draws its breath,

And feels its life in every limb,

What should information technology know of death?I met a footling cottage Daughter:

She was viii years old, she said;

Her hair was thick with many a curl

That clustered round her head.She had a rustic, woodland air,

And she was wildly clad:

Her eyes were fair, and very off-white;

—Her beauty made me glad. (ane-12)

In the fourth stanza, dialogue gets under manner, with a question from the verse form's speaker and an answer from the girl:

"Sisters and brothers, little Maid,

How many may y'all exist?"

"How many? Seven in all," she said

And wondering looked at me. (13-16)

From here, the poem comprises dialogue between speaker and kid. Repeatedly the speaker proposes to the girl that there are five children in her family unit, because two take died, and repeatedly the kid asserts, "We are 7," elaborating upon her argument until, near the end of the poem (stanzas xi-12), she tells how she knits and eats by the graves of her siblings and then (stanzas xiii-xv) narrates the death of a brother and sister.

Formally, "We Are Seven" has affinities with "Gipsy Kid," for while it is in ballad meter (alternating tetrameter and trimeter), its rhyme scheme (of a-b-a-b) and its length of seventeen stanzas are reiterated in Arnold'south poem. And Wordsworth also revised his poem to shift its form of address. In 1815, he changed the original opening line, "A simple child, dear brother Jim"—Coleridge's line, as Wordsworth explained, from an opening that Coleridge "threw off" and that addressed their friend James Tobin (Wordsworth 947)—to the elliptically shortened line that makes the poem less occasional. These formal affinities requite united states of america a basis for comparing the two poems that extends beyond the presence in each of a child figure. Using U. C. Knoepflmacher's terms, we tin can recognize the affinities equally role of a "Wordsworthian matrix" in Arnold's work that has the role of demurring: enabling "what essentially amounts to a denial of the vision of Arnold's predecessor" (47). Only the demurring here is centrally formal, rather than thematic.

Each poem has a basis in an bodily meet, Arnold'due south in the occasion Tom relates and Wordsworth's in a conversation in 1793 with a girl at ![]() Goodrich Castle (Wordsworth 947), but the bamboozlement of the poems in representing lived feel differs. Wordsworth's poem values the creation of a dramatic situation, and its clarification of the kid—her age, her curls, her being "wildly dressed," her eyes "fair, and very fair" and the impression of "beauty" made upon the speaker—serve this end. We are meant from the start to visualize the "Simple Child" and to carry an prototype of her into the conversation that ensues, in which the poem's speaker has fewer (and less varied) words than the child. His remarks and questions elucidate her belief, and, as her responses grow more than involved, the poem privileges the revelation of her feel.

Goodrich Castle (Wordsworth 947), but the bamboozlement of the poems in representing lived feel differs. Wordsworth's poem values the creation of a dramatic situation, and its clarification of the kid—her age, her curls, her being "wildly dressed," her eyes "fair, and very fair" and the impression of "beauty" made upon the speaker—serve this end. We are meant from the start to visualize the "Simple Child" and to carry an prototype of her into the conversation that ensues, in which the poem's speaker has fewer (and less varied) words than the child. His remarks and questions elucidate her belief, and, as her responses grow more than involved, the poem privileges the revelation of her feel.

"Gipsy Child" is quite different, both in what it values and how it communicates the valuation, and lying at the heart of the rhetorically strained impression the poem makes is its syntactically suspended penultimate sentence, which seals the speaker'southward closing identity every bit a alone discourser. Not only is at that place the situational problem (then different from the problem of "We Are Vii") that a "kid" would not be able to empathise the abstractions addressed to it but there is also the style those very words sublimate the child effigy: that is, how they switch the effigy from a physically present accountant into a conceptual condition of the verse form. The judgement's repeated "though" becomes a lever propelling the verse form abroad from its kid effigy, implying that the poem has something to say without the listener and forcing the reader into an uncomfortable syntactic and conceptual suspension:

And though k glean, what strenuous gleaners may,

In the throng'd fields where winning comes by strife;

And though the just sun order, every bit mortals pray,

Some reaches of thy tempest-vext stream of life;Though that blank sunshine blind thee; though the deject

That sever'd the world's march and thine, exist gone;

Though ease dulls grace, and Wisdom be as well proud

To halve a lodging that was all her own—Once, ere the day decline, thousand shalt discern,

Oh in one case, ere nighttime, in thy success, thy chain! (57-66)

What success and what chain? a reader of this penultimate sentence might well enquire. The poem has changed its rhetorical orientation towards the situation and scene with which it began, opening into a globe without dialogue and into a figurative landscape where "Douglas, Mann" has little relevance as a locale.

Accomplishing this re-orientation, the poem destabilizes itself. Virginia Jackson remarks that "where or who 'you' are makes a difference in, among other things, historical questions of genre" (119), and as "Gipsy Child" thinks through forms of accost, invoking a possible mode of dialogue that it and so rejects, information technology discovers a project of irresolute its interlocutor from a grapheme, a person in the poem, into a circumstance, a condition of it. Involved in a radical transformation of the where and who of its "you," information technology becomes a hard poem to allocate.

This destabilization separates it from other poems and poetic modes that it invokes. Wordsworth's "To H. C. Vi Years Old," for example, addresses a child, simply is a conventional poem of apostrophe that lacks the rhetorical transformation of "Gipsy Child." From its first lines, "To H. C." offers an accumulation of apostrophic exclamations which communicate that its addressee will not answer:

O thou! whose fancies from afar are brought;

Who of thy words dost make a mock apparel,

And fittest to unutterable thought

The breeze-like motion and the self-born carol;

Thou faery voyager! (1-5)

Further, while "To H. C." bears a thematic resemblance to "Gipsy Child" in its pondering of a child's hereafter, it does non share Arnold's interrogative mode. Wordsworth'due south poem contains simply ane question, three-quarters of the way through, of a uncomplicated variety: "What hast one thousand to do with sorrow,/ Or the injuries of tomorrow?/ Thousand art a dew-drop, which the morning brings forth" (25-seven). This is a rhetorical question embedded in a poem; we run across at once that the reply is very little.

Perhaps we might try to identify "Gipsy Child" as a poem of apostrophe based on its late movement into that way. Only if we accept the definition of apostrophe as "[p]oetic address, especially to unhearing entities, whether these exist abstractions, inanimate objects, animals, infants, or absent or dead people" (Waters 61), its significant innovation upon the blazon becomes evident. The kid every bit first addressed by the poem seems to be a hearing (and potentially speaking) entity; Arnold highlights the possibility of response past making this addressee pointedly a "child" (who might understand and answer), not an "infant" (who would non), although accounts propose that his existent-world encounter was with an baby also young for speech. Tom Arnold writes that the child seen on the Mann was held in its mother's arms "looking backwards over her shoulder" (Tom Arnold 8), every bit a baby might exist, and Ian Hamilton identifies the child as a "babe girl" (Hamilton 90). Information technology is interesting to annotation an apparent inconsistency—the verse form's utilize of "child" even every bit evidence suggests "babe" may have been the more accurate Victorian designation—in low-cal of Arnold's eventual work as inspector of schools, where he scrupulously drew a distinction between those terms.[eight] In choosing "child," Arnold entertains the possibility that this leaseholder might listen and reply.

How old was the child, and how one-time is the child? Every bit Tom Arnold's account reminds us, "Gipsy Kid" raises questions about the relationship between events and poetic representation. His remarks provide the clearest evidence nosotros accept of a relationship between the poem and his brother's real-earth experience. Yet doubt inheres even hither: over when the encounter happened, over how long after it he began to write, over precisely what he saw. The poem's rhetorical shift from an opening proffer of situation and dialogue toward a climax centered in interiority and lonely soapbox asks us to retrieve about the relationship between outside and inside, posing a query about how and how much encounters in the external world matter for a poet. Nosotros practise not take to put the remark in its crudest form (he tries to talk to a kid, and all he can do is think his own thoughts) to see the problem the poem ponders: in what sense will the poem make the encounter affair? And, corollary to that: in what sense is poetic "encounter" an encounter at all? These inquiries lie inside the "You lot may well ask!" that Hollander imputes to an opening question. With Arnold'due south predecessors in mind, nosotros can frame the enquiry another way. What, for "Gypsy Child," is the "event" that Coleridge and Wordsworth made so central to lyric verse? We have some evidence that Arnold at some point noticed a child in Douglas, Island of Human being. Is that sighting the event? Is the event the conversion of such a sighting into poetic come across? How does the rhetorical transformation within the poem relate to "real-globe" happenings?

Jackson's observation that over-determined narratives of lyric development obscure a complex procedure of poetic contention with the problems of addressing others suggests how we might value "Gipsy Kid" as a verse form of lyric transition: "What has been left out of most thinking about the process of lyricization is that it is an uneven series of negotiations of many different forms of circulation and address," she writes (Jackson eight). "Gipsy Child" inhabits precisely such complication and might be envisioned, if not as a point on a timeline, then equally ane among a nexus of lyric gateways. If we say that the poem participates in a recurring "theme of conscious tragedy" (Trilling 96), or that it uses the culturally foreign figure of the Gypsy to ponder issues of estrangement, so considering the verse form's constitutive formal problem and action—its struggle with intersubjectivity and its consistent assay in lyric exercise—can merely overstate our understanding. For Arnold, the formal struggle and experiment relate to the conditions of tragedy and alienation: to his confidence that an platonic relationship among author, text, and audition had been lost and to a growing sense that English language poets could no longer speak to their society in germane ways, that exercise of the art assured their status as ineffectual outsiders. "Gipsy Child" discovers an idiosyncratic mode every bit it transforms its questioning speaker into a lonely discourser. "By 'lyric' I mean the illusion in an artwork of a atypical voice or viewpoint, uninterrupted, absolute, laying claim to a world of its own," writes T. J. Clark. In the poetic metamorphoses it fashions out of a seaside feel of (perchance) 1843, "Gipsy Child" directs our attending to the illusion of "a atypical vox. . . laying claim to a world," and so information technology becomes a poem in which we hear "sinews cracking."

published Oct 2014

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Drury, Annmarie. "'To a Gipsy Kid by the Bounding main-Shore' (1849) and Matthew Arnold's Poetic Questions." BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Hither, add your last engagement of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Abrams, Thou. H. "Structure and Style in the Greater Romantic Lyric."The Correspondent Breeze: Essays on English language Romanticism. New York: Norton, 1984. 76-108. Print.

Allott, Kenneth. "Matthew Arnold's Reading-Lists in Three Early Diaries." Victorian Studies 2.3 (1959): 254-66. JSTOR. Web. 25 March 2013.

Arnold, Matthew. Collected Prose Works. Ed. R. H. Super. Vol. two. Ann Arbor: Academy of Michigan Press, 1962. Impress.

—. The Letters of Matthew Arnold. Ed. Cecil Y. Lang. Vol. 1. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996.

—. The Note-Books of Matthew Arnold. Ed. Howard Foster Lowry, Karl Young, and Waldo Hilary Dunn. London: Oxford UP, 1952. Print.

—. "Notes made in Arnold'southward chapters equally Inspector of Schools." Matthew Arnold Drove, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University=. GEN MSS 867, box ii.

—. "Preface to Poems, Edition of 1853." The Portable Matthew Arnold. Ed. Lionel Trilling. New York: Viking, 1949. 185-202. Impress.

—. The Strayed Reveller, and Other Poems. London: B. Fellowes, 1849. Print.

—. "To a Gipsy Child Past the Sea-Shore." Victorian Verse and Poetics. Ed. Walter Houghton. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1968. 411-12. Impress.

[Arnold, Tom.] "Matthew Arnold." The Manchester Guardian 18 May 1888: 8. ProQuest. Historical Newspapers The Guardian and The Observer (1791-2003). Web. 3 Apr 2013.

Blake, William. "The Tyger." The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman. New York: Anchor, 1988. 24-5. Print.

Clark, T. J. Goodbye to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism. New Haven: Yale UP, 1999. Print.

Hamilton, Ian. A Gift Imprisoned: The Poetic Life of Matthew Arnold. London: Bloomsbury, 1998. Print.

Harrison, Antony H. The Cultural Product of Matthew Arnold. Athens, OH: Ohio Up, 2009. Print.

Haskins, Ekaterina V. "Philosophy, Rhetoric, and Cultural Retention: Rereading Plato's Menexenus and Isocrates' Panegyricus." Rhetoric Club Quarterly 35.1 (2005): 25-45. JSTOR. Web. 29 May 2014.

Hollander, John. Melodious Guile: Fictive Pattern in Poetic Language. New Haven: Yale Up, 1988. Print.

Jackson, Virginia. Dickinson'south Misery: A Theory of Lyric Reading. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2005. Print.

Keats, John. The Poems of John Keats. Ed. Jack Stillinger. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 1978. Print.

Knoepflmacher, U. C. "Dover Revisited: The Wordsworthian Matrix in the Poesy of Matthew Arnold." Matthew Arnold: A Collection of Disquisitional Essays. Ed. David J. DeLaura. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1973. 46-53. Impress.

Murray, Nicholas. A Life of Matthew Arnold. New York: St. Martins, 1996. Print.

Russell, David. "Teaching Tact: Matthew Arnold on Instruction." Raritan 32.3 (2013): 122-39. Impress.

Saintsbury, George. Matthew Arnold. Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1899. Print.

Socrates. The Collected Dialogues of Plato. Ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1961. Print.

Trilling, Lionel. Matthew Arnold. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia Upwardly, 1949. Print.

Waters, William. "Apostrophe." The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poesy and Poetics. 4th ed. Ed. Roland Greene et al. Princeton: Princeton Upwardly, 2012. 61-2. Print.

Wilder, Lance. "Un-Gypsying the Gypsies: Arnold's Wandering Metaphor of Fourth dimension." Philological Quarterly 87.3-4 (2008): 389-413. Academic Search Complete. Web. 25 Feb. 2013.

Wolfson, Susan J. The Questioning Presence: Wordsworth, Keats, and the Interrogative Mode in Romantic Poetry. Ithaca: Cornell Upwards, 1986. Print.

Wordsworth, William. William Wordsworth: The Poems. Ed. John O. Hayden. Vol. 1. New Oasis: Yale UP, 1981. Print.

ENDNOTES

[one] Among the poems that Hollander (23-twoscore) enumerates are many of Shakespeare'south sonnets, canto 4, volume 3 of Edmund Spenser's Fairie Queene ("Where is the Antique celebrity now become,/ That whilome wont in women to appeare?"), and the young George Herbert's sonnet that opens, "My God, where is that ancient heat towards Thee/ Wherewith whole shoals of martyrs once did fire/ Besides their other flames?"

[2] Offset editions bear the engagement 1855, but the book actually appeared in Dec 1854 (Murray 146). Murray identifies August 1843 as the probable date of limerick for "Gipsy Kid" simply suggests 1845 would also exist possible (49, 50).

[three] The relatively curt chronology for Arnold'southward writing (as distinct from publication) of poetry runs from the early on 1840s until most 1860, from which year he scarcely wrote poems. While the appointment of composition for "Dover Beach" is non known with certainty, 1851 is generally accepted as likely, situating the poem near the middle of the timeline.

[4] Ekaterina V. Haskins writes that "many agree that Menexenus serves as both a condemnation of Athenian democracy in its current state and an indictment of the very language that perpetuates the vanity and insolence of Athenian citizens and the Athenian foreign policy." She argues, farther, that Plato employs conventions of the funeral speech as office of a projection to "construct the identity of a philosopher" (26, 27).

[v] At first, under the influence of a speech repeated to him past Phaedrus, he compares the value of the "lover" and the "nonlover" to find the lover lacking. His 2d speech, a "recantation" (Socrates 502) of the beginning, enters into a metaphorical mode (his figure of the soul as 2 horses and a charioteer is important hither) to extol dear.

[6] Arnold quotes in Greek. I use the translation of Paul Shorey (602-3); the passage is from Book I, 352d.

[7] The term appears in Arnold's papers in the Beinecke Library, Yale University, in autograph notes (GEN MSS 867, box 2). It seems hither to be used past a colleague of Arnold's, who remarks on the quality of the "answering in History" at a school in ![]() Bethnal Green.

Bethnal Green.

[viii] Arnold drew the distinction between "infant" and "child," for example, in a letter to the Daily News in March of 1862. Objecting to the Revised Code that aimed to make school funding dependent upon examination results, he writes: "In London, in a school filled with the children (not infants) of poor weavers of ![]() Spitalfields, every child volition under the Revised Code be examined past the Inspector" (Arnold, Collected Prose 246).

Spitalfields, every child volition under the Revised Code be examined past the Inspector" (Arnold, Collected Prose 246).

Source: https://branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=annmarie-drury-to-a-gipsy-child-by-the-sea-shore-1849-and-matthew-arnolds-poetic-questions

0 Response to "They Are All Gone and Thou Art Gone as Well! Yes Thou Art Gone! Matthew Arnold"

Post a Comment